The sharps and flats show what the whole-steop/half-setp arragnement is in each scale. 1800 BC to the middle of the 1st millennium. It is not a stretch of the imagination to suggest that the ancient Greeks did, as Pythagoras said, learn Mesopotamian music theory-together with their mathematics-in the Near East.įig. We also know that the Sumero-Babylonian musical system was exported at least as far away as the Mediterranean coast, for the same Akkadian corpus of terms was used for instructions to instrumentalists performing Hurrian cult hymns in ancient Ugarit (modern Ras Sham) in Syria. 1800-500 BO had earlier Sumerian antecedents, because many of the technical terms in Akkadian have Sumerian equivalents. It is highly probable that the tuning systems evidenced in the Akkadian language in texts dating from the Old Babylonian to the Neo-Babylonian period (ca. Two of these important technical texts came from the site of Ur, while three others came from another rich Sumerian site, the ancient city of Nippur. But research on the part of several cuneiformists and musicologists working together has been strengthened over the years by the steady accumulation of cuneiform tablets that use the same standard corpus of Akkadian terms to designate the names of the musical strings the names of the instruments and their parts fingering techniques the names of musical intervals (fifths, fourths, thirds, and sixths) and the names of the seven scales that derive their nomenclature from the particular interval of a fourth or a fifth on which the tuning procedure starts. ) seemed difficult for many to believe (Fig. The fact that these seven scales could be equated with seven ancient Greek scales (dating some 1400 years later) quite startled the scholarly community and the fact that one of the scales in common use was equivalent to our own modern major scale (do-re-mi. 1800 BC, or about 850 years after the period of the Royal Cemetery of Ur), there existed standardized tuning procedures that operated within a heptatonic, diatonic system consisting of seven different and interrelated scales (see box with Glossary of Musical Terms).

We now know that by the Old Babylonian period in ancient Iraq (i.e., by at least ca. 5) that contain technical information about ancient musical scales. Thus far, cuneiformists have identified ten Mesopotamian tablets (Fig. Scales and Tuning in Ancient MusicĪmong the many cuneiform tablets studied we have been fortunate to have recognized, since 1959, a small number of texts that relate to the tuning and playing of ancient instruments (see map on p. The bovine lyre was represented in the graves at Ur by instruments ranging in size from small examples that would have been hand-held to the well-known lyre with the lapis lazuli-bearded bull’s head, the largest of the lyres recovered (Fig.

(The heads of some resemble bearded bison.) Other bovine lyre bodies are more schematic: the actual soundbox has a trapezoidal or rectangular shape with a realistic bovine head appended to the front (Fig. Its soundbox is usually in the shape of a realistic reclining or standing bovine. The bovine lyre was the most common stringed instrument of the mid-3rd millennium BC in the Near East. On a lyre, the strings run over a resonating chamber, or soundbox, to a yoke (for more on lyres and harps, see de Schauensee, this issue).

The large Bull-Headed Lyre, with its long strings, would have sounded something like a vass viol. The medium-sized silver bovine lyre now in the British Museum might have sounded like a cello. Thus, we now have concrete evidence we can use to replicate these unique lyres and harps (see below).įig.

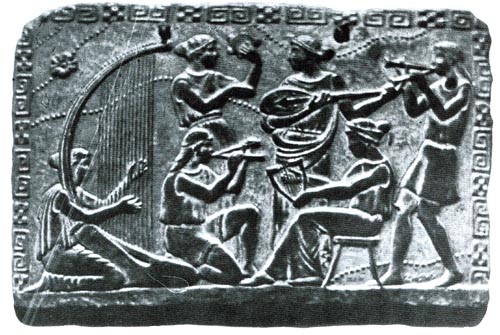

As a result of many years of study by archaeologists and museum researchers, we now believe we have correctly separated the different and distinct instruments and improved our assessments of their original sizes. When the ceilings of the ancient tombs fell in, some of the instruments collapsed together so badly that it was difficult to sort out which pieces went with which (see Fig. It is these materials that enabled the excavators to establish the forms and dimensions of the instruments. The original wooden stringed instruments found at Ur were richly decorated or overlaid with gold, silver, copper, lapis lazuli, mother of pearl, and other non-wood materials that did not deteriorate in the earth over the millennia. The top register shows festive banqueters. In the bottom register are 2 “cymbalists” (figures palying clappers), a dancer, and a seated figure playing a bovine lyre. Scene on a gold cylinder seal from a grave in the Ur cemetery (PG 1054).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)